As I near the end of EDCI 568, I find myself reflecting not just on what I’ve learned, but on how I’ve changed. This course has invited me to step into deeper inquiry, both professionally and personally, particularly around my work as a long-time educator in elementary math. I came in with questions about how best to meet the needs of students, especially those who struggle with math anxiety. I’m leaving with an enriched understanding of how design, openness, digital tools, and cognitive science all intersect within the BC curriculum to shape learning experiences, and how, as a teacher, I have both a responsibility and an opportunity to engage critically with these forces.

Math Anxiety and the B.C. Core Competencies

Beilock and Maloney’s (2015) work on math anxiety was a pivotal reading for me. I’ve always understood that emotions play a role in learning, but their argument, coming from a neuroscience and psychology point, gave language and legitimacy to what I’ve seen over and over in my classroom. Anxiety physically disrupts working memory. When students feel panic, they can’t access the very reasoning strategies we’re trying to teach. In BC’s revised curriculum, which emphasizes thinking, personal awareness, and social responsibility through the Core Competencies, I now see a built-in opportunity to address this.

When students reflect on their personal awareness, they’re not just complying with SEL expectations—they’re learning to identify and manage the anxiety that affects their cognitive load. These reflections create space for metacognitive conversations about frustration, mistakes, and perseverance, especially in math. By integrating Core Competencies into math instruction explicitly, I’ve begun to shift from viewing math learning as content-driven to seeing it as identity-driven.

Cognitive Load Theory vs. Inquiry-Based Learning

This shift also prompted me to explore a question that has long divided educators: Do we overload students with open-ended inquiry, or do we restrict their potential by over-scaffolding? Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) warns us that novice learners can become overwhelmed when asked to solve problems without sufficient guidance. But the BC math curriculum asks us to teach through big ideas and conceptual understanding—approaches aligned more with inquiry-based learning (IBL).

Rather than seeing CLT and IBL as opposites, I now recognize the value in blending them. Sweller’s theory doesn’t reject inquiry—it simply reminds us that timing and scaffolding matter. In early stages of a math unit, I now offer structured tasks with low cognitive demand. But I build toward open-ended problems that invite divergent thinking and authentic inquiry. This way, I respect students’ cognitive development and the curriculum’s emphasis on conceptual understanding.

This blend is perhaps best captured through project-based learning (PBL).

Project Based Learning and the Open Hub Model

PBL isn’t new, but EDCI 568 helped me reframe it within open learning contexts. Through class readings and discussions, I was introduced to the Open Hub Model, a framework where learners gather around shared interests, resources, and problems, connecting in a “hub” of dialogue, while moving outward to apply learning in real-world contexts. This model closely aligns with the learner-driven nature of PBL. It assumes that learners are capable, curious, and connected.

What I didn’t realize until recently is that this open sharing can also be seen as a political and ethical act.

Digital Identity, Rights, and Responsibilities

EDCI 568 prompted deep thinking about what it means to engage in digital, networked, and open learning environments. As teachers, we hold tremendous responsibility when introducing students to online spaces. I read DeGroot, Young, & VanSlette’s (2015) study on instructors’ social media use and was struck by the parallels to K-12 education. Their research showed that when instructors engage authentically online, students perceive them as more credible, human, and approachable.

This resonates with my own social media use as an educator. I’ve used some media platforms to connect with other math teachers, sharing strategies, questions, and even failures. When done transparently and ethically, this kind of engagement models digital citizenship for students. But it also raises questions: How do we protect student privacy in public-facing projects? How do we teach them to think critically about the platforms they use?

These are the tensions I now navigate more intentionally. The goal is not to shield students from the digital world, but to mentor them through it.

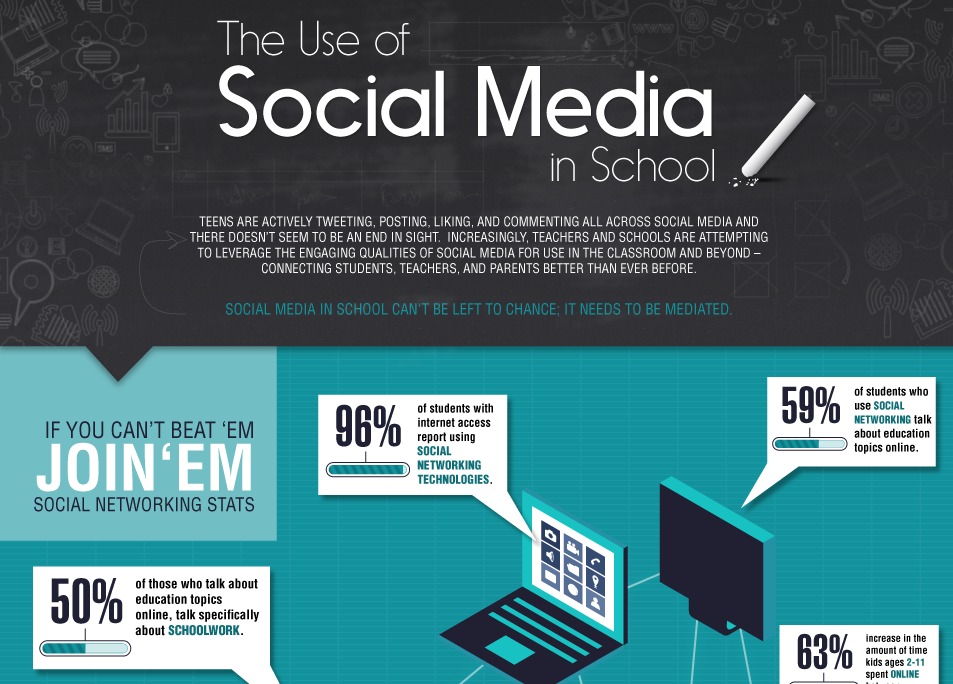

Embracing Social Media in Education

One of the clearest takeaways from this course is that social media is not going away. As educators, we need to stop avoiding it and start using it with purpose. Social media platforms are now a central part of how students communicate, learn, and even form their identities. Rather than seeing these platforms as distractions, we can approach them as learning tools, spaces for connection, and opportunities to model digital citizenship. For teachers, engaging with social media professionally opens doors to collaboration, ongoing professional learning, and access to rich, diverse teaching resources. It also invites is to share our practice transparently, contributing to a broader culture of openness in education. While there are risks and challenges, ignoring these spaces doesn’t make them safer for students, instead it leaves them to navigate the digital world without the guidance of thoughtful, informed adults. As teachers in 2025, and beyond, we must be willing to learn alongside our students and help them use these tools ethically, creatively and critically.

Reconciling Learner Needs and Systemic Pressures

A recurring theme in many of my readings for this course has been the disconnect between the learner and the system. The BC curriculum gives us freedom through its flexible, concept based design. But the system still prioritizes outcomes, assessment and standardization. Learners are often squeezed between these forces. As a teacher it is my job to navigate my lessons around these forces while allowing my students to grow and learn. I need to ask myself better questions as I am planning, such as:

How do I create learning environments that reduce anxiety while still maintaining expectations?

How do I empower students to inquire without overwhelming their thinking process?

How do I model openness while protecting boundaries?

These are not problems to solve once, but questions to ask regularly.

Where am I Now

Where I am now is somewhere between structure and freedom, between design and emergence. I still love the clean precision of a well scaffolded math lesson. But I also love the messy, surprising energy of an inquiry that takes us somewhere I didn’t expect. More than anything, EDCI 568 has deepened my identity as a teacher. Someone who doesn’t just deliver content but constantly examines, questions, and evolves practice. I’m more curious about learning design, more questioning of the systems that shape it, and more hopeful about the role digital and open tools can play in making education more human, more equitable, and more responsive to the learners in front of me.

I don’t know all the answers, but I know that asking better questions, and asking them openly, is where transformative education begins.

References

Barron, Dr Brigid. “A Review of Research on Inquiry-Based and Cooperative Learning,” n.d.

Beilock, Sian L., and Erin A. Maloney. “Math Anxiety: A Factor in Math Achievement Not to Be Ignored.” Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2, no. 1 (October 2015): 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732215601438.

DeGroot, Jocelyn M., Young ,Valerie J., and Sarah H. and VanSlette. “Twitter Use and Its Effects on Student Perception of Instructor Credibility.” Communication Education 64, no. 4 (October 2, 2015): 419–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2015.1014386.

Graham, Lee, and Verena Roberts. “SHARING A PRAGMATIC NETWORKED MODEL FOR OPEN PEDAGOGY: THE OPEN HUB MODEL OF KNOWLEDGE GENERATION IN HIGHER-EDUCATION ENVIRONMENTS.” International Journal on Innovations in Online Education 2, no. 3 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1615/IntJInnovOnlineEdu.2019029340.

Kirschner, Paul A., Sweller ,John, and Richard E. and Clark. “Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work: An Analysis of the Failure of Constructivist, Discovery, Problem-Based, Experiential, and Inquiry-Based Teaching.” Educational Psychologist 41, no. 2 (June 1, 2006): 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1.

Maloney, Erin A., and Sian L. Beilock. “Math Anxiety: Who Has It, Why It Develops, and How to Guard against It.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 16, no. 8 (August 2012): 404–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.06.008.

Ramirez, Gerardo, Elizabeth A. Gunderson, Susan C. Levine, and Sian L. Beilock. “Math Anxiety, Working Memory, and Math Achievement in Early Elementary School.” Journal of Cognition and Development 14, no. 2 (April 2013): 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248372.2012.664593.

Swars, Susan Lee, C.j. Daane, and Judy Giesen. “Mathematics Anxiety and Mathematics Teacher Efficacy: What Is the Relationship in Elementary Preservice Teachers?” School Science and Mathematics 106, no. 7 (2006): 306–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1949-8594.2006.tb17921.x.

Leave a Reply